Knowing Your Yeats from Your Philpotts: Intellectual Integrity and the Fight Against Mis/Disinformation

This week, I have been planning a post about a lovely little quote about the universe and how it wants us to sharpen up our wits. It has one of my favorite words in it–magic–so you’d think I would use this line to invite you to find magic in the year to come.

Actually, no.

Instead, I was going to tell you all about how this sentence is mistakenly attributed to W.B.Yeats (all the time!), when, in reality, it was written by another 19th century white guy who you have never heard of.

I was going to tell you how even my university’s Irish Studies department slapped this quote under a photo of a young Willie Yeats on Instagram. I was considering telling you how I know my Yeats so well (thanks to that same department) that I was sure he wouldn’t say such a thing in such a way. I was going to tell you how all kinds of smart people don’t know their dead Irish poets and clearly haven’t done their research, because this misattribution has been propagating for years (and it has driven me crazy all along).

But honestly, who cares?

This obsessive need to nail the citations, button up all the grammar, and perfect the formatting is tiresome, don’t you think? The not-so-subtle self congratulatory nature of pointing out that I am a well-educated poetry geek who is smarter than a social media manager is kinda gross, isn’t it? And don’t we all have better things to worry about than the feelings of long dead dudes who were born in British colonies?

Before we go on, since I know you’re dying to know who said “The universe is full of magical things, patiently waiting for our wits to grow sharper”: it was Eden Philpotts, an Indian born British writer who I only know about because of Wikipedia. I did track down the original source of the quote (because I am insufferable and enjoy procrastination techniques that involve using the search feature in PDFs of obscure manuscripts). I will never read A Shadow Passes, but I did read the entire paragraph on page 19 that includes the quote.

Once again: so what? Ultimately, instead of sweating the small stuff, isn’t it more important to engage with the idea that the universe really is waiting for our wits to grow sharper so we can see all the magical things? I mean, research is all well and good, but what we really need is to see the world through the eyes of the soul and navigate according to our dreams, right?

Well, yes, of course!

And, well, not exactly.

In 2022, we need to know the difference between truth and belief (and it’s even more important than knowing your Yeats from your Philpotts)

We all know that we live in an age when “facts” seem debatable. It’s old news to hear that lots of the news is fake news. “Science” is a kickball and the arguments being waged over that word have nothing to do with peer review. And then there is truth, which means something different to nearly everyone, especially when you spell it with a capital “T.”

That last example? Where “truth” becomes more a matter of personal conviction than the opposite of a verifiable lie? Yeah, I have been guilty of tossing that word around and helping to render it a little more meaningless. And I know I’m not the only writer/healer/transformation professional who is contributing to substituting “personal truth” when we really mean “belief.”

I think we can all get better about making those distinctions and continuing to ask questions and offer answers accordingly as we move forward.

So yeah… I am not writing that post because, in the grand scheme of things, mixing up a Nobel Prize winning poet and a minor author, both born in the 1860s, is a laughably minor offense. If anything, it shows the college professors and librarians their own enduring value, even with the world of knowledge available at the other end of a search string.

Here’s the real question: how do we tell the difference between the data we need to verify and the ideas we can share with impunity?

Obviously, if it’s a matter of life and death, like public health or an attempted coup election security, we should verify our sources and proofread all the names, dates, and figures.

Oh, wait, it’s the 2020s. “Obviously” does not apply in such cases. At least it seems that many folks with microphones and social media platforms don’t think so as conspiracy and conjecture get passed along, emotionalized, and amplified.

I’m with you: I don’t know how to take on the disinformation, the endless arguments, the cognitive dissonance, the torrents of bad faith.

All too often, I sit with the great lie we learned on the playground: “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me. I just get sucked into the constant questioning… Are we going to be OK or are we doomed? Are we treating a paper cut when the patient is in cardiac arrest? Are we all fighting over place settings while the kitchen is on fire?

As we all struggle with the most impossible social divides, let me stick to what I know today: literature, the construction of ideas, and the role of the creative.

Remember, Anonymous Was a Woman

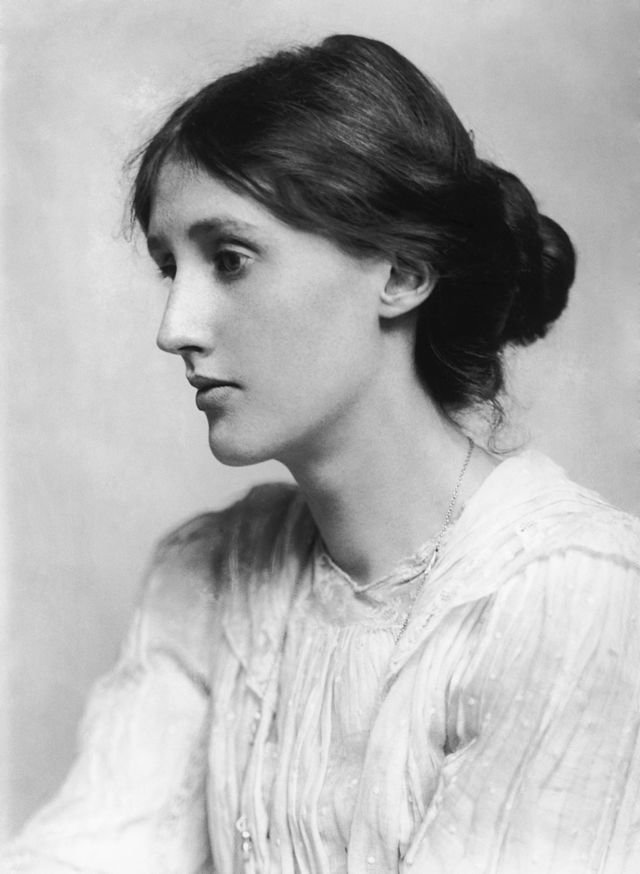

Ok, so the internet seems to recall that Virginia Woolf expressed this now iconic idea in A Room of One's Own. At least, we all agree to the snappier paraphrasing and appreciate that she said, "I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman."

When we stop caring about who said what or we just accept the Instagrammable meme version of a quote or a statistic, we lose something.

It may just be an Irish Studies department losing the respect of its alumni. We might lose some of our own intellectual integrity. After all, we would hope that when we say something quotable, draw something sharable, or create something meme-able, we get a shout out and a link to our Insta.

We might lose something even more valuable, if, for example, we believe or share unverified theories or outright lies about what really matters, like climate change, vaccine safety, insurrection mobs, or voter suppression figures.

What if we build out intellectual integrity by seeking proper attribution and getting the damn quote right?

‘And wisdom is a butterfly

And not a gloomy bird of prey.’

Those are actual lines from Yeats, from his poem “Tom O’Roughley.” I’ve long held this idea close to my heart because I hate to see “superior” knowledge used as a weapon. I think we all know what it’s like to be both the bird and the prey, and I think we recognize the suffering that comes to all in such situations.

We don’t need to get all nasty and pedantic in this quest to do better. Instead, in this age of mis- and disinformation, I invite you to join me and advocate for just a bit more intellectual integrity.

It doesn’t have to mean jumping into the scrum on your cousin’s Facebook feed or calling out the wellness influencer you used to love who has started to call the Covid-19 vaccine a bioweapon. (But really, the vaccine is not a bioweapon and maybe more people need to hear that.)

You can begin this quest for integrity by looking a little deeper before you share a cool line from the Facebook feed or from that first page of result on those crazy quote directories.

Besides uncovering misattributions or realizing that the line really did have a source and wasn’t written by Anonymous, here’s what you may discover…

The person who actually said this wonderful thing was/is a Nazi sympathizer, an abuser, a total creep. (Warning: you may uncover things you didn’t want to know. Coco Chanel, Marian Zimmer Bradley, and Gandhi all spring to mind immediately.)

The context of the line “everyone” loves to quote makes a tremendous difference and reading the whole piece, or at least the rest of the paragraph may alter your decision to share that one line that caught your fancy

Getting Maya Angelou quotes right matters

Here’s one last story about my quote sleuthing hobby (and proof that I worked at a college library throughout my twenties and was learning the trade when I wasn’t in my office blogging about epiphanies).

There’s an oft-quoted line by the legendary Maya Angelou: "No man can know where he is going unless he knows exactly where he has been and exactly how he arrived at his present place.”

You’ve seen it. I promise. It’s used by brilliant, well-meaning people to brilliant effect all the time. I just came across it most recently in Resmaa Menakem’s My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies.

Here’s the slightly more complete version that is often shared only during Black History Month or articles specific to the Black experience: “For Africa to me... is more than a glamorous fact. It is a historical truth. No man can know where he is going unless he knows exactly where he has been and exactly how he arrived at his present place.”

My gods, it is a powerful line and it does speak to the entire human experience, but everyone’s first favorite Black woman poet (besides Amanda Gorman) wasn’t talking about the journey of life, she was talking about the (forced) journey from her ancestors’ particular homeland. And that matters.

It takes some patience to actually find the source of this passage (which is always attributed to Angelou with the ellipses, but never actually names the source). It’s an article from Section D, Page 15 of the New York Times from April 16, 1972. But, again, so what?

Well, I find it pretty damn revealing to note that the name of the piece is “For Years, We Hated Ourselves.”

Angelou is reviewing a four-part documentary series, “Black American Heritage,” by Eliot Elisofon, a white photographer who sounds like an utter egomaniac who also had a deep respect for the people and culture of Africa.

In the course of the review, Angelou gives us a glimpse of her own experience of being a Black American, who grew up learning how to act white and dread pagan Africa until the massive changes of the mid-1950s that inspired folks to ask “If Black is Beautiful, where has it been all this time?”

I encourage you to read the whole article and marvel that it was written fifty years ago, to sit with all that has changed, and to reckon with how few things are different.

Because, indeed, to paraphrase the great Maya Angelou in the hope of providing her words the context and respect they deserve, we cannot know where we are going unless we know exactly where we have been and exactly how we arrived at our present place.

And that is true in the deeply specific and personal, as well as the collective, universal relationship to this whole swath of human history, experience, and future.