BLOG

Dance Camp by Guest Storyteller Sara Eisenberg

I walk into the plain box that is the main studio bearing a small notebook, a water bottle, and a body trained from age four to classical ballet’s five stylized positions - turned-out hips, port de bras and all. Ignorant of the terminology, elements, rules, of modern dance. Ready to risk moving in unaccustomed ways. Age 68. De-conditioned.

I walk into the plain box that is the main studio bearing a small notebook, a water bottle, and a body trained from age four to classical ballet’s five stylized positions - turned-out hips, port de bras and all. Ignorant of the terminology, elements, rules, of modern dance. Ready to risk moving in unaccustomed ways. Age 68. De-conditioned.

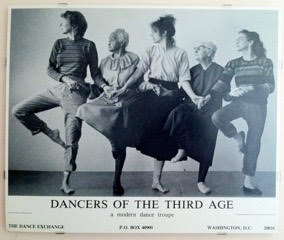

Am I nuts? Or am I home? I am a Dancer of the Third Age, captured by this iconic image that hangs on my wall.

Am I nuts? Or am I home? I am a Dancer of the Third Age, captured by this iconic image that hangs on my wall.

It’s taken me 28 years to drive 42 miles to the Dance Exchange, but here I am.

We move out from the opening circle walking randomly, casually pair up for counter-weight stretches, grasp with hands or elbows, pull away. Keep moving, lean on and into one another, form shifting sculptures of three or four. Flock together, following the changing leader, ever shifting to sync with other bodies. Practice not replicating but capturing the essence of a partner’s movement. Preliminaries to creating dance together.

We tell our stories and “found” gestures emerge - a sweep of the arm, a shift in gaze, height, level, or direction. We play with these gestures like words snipped from magazines, and build movement phrases, sequences, experiment with them as solos, duets, chorus. Later, spoken words are layered in. Even later, music.

I am unmoored by the absence of music. Sequence flusters me. Brow furrowed, I ask again: break this down for me. Ever seeking flow and smoothness, I am immersed in this staccato movement all week: break it down, re-member a sequence, work it through. Others waiting for me. Waiting. Waiting.

Still, I am willing to be the only one standing when everyone else drops to the floor, to forgo a jump and instead lift a leg, to drop a movement altogether.

I walk out of the studio at the end of camp with a few scribbles in my notebook, an empty water bottle, and no injuries. Praising.

Limitations have become less encumbrances than shifting opportunities to shape choreography, relationship, life. Secret chords that please: Hallelujah gestures, broken down, broken open, holy.

Sara Eisenberg grapples with honesty and kindness in daily life in Baltimore, where she practices as a healer, herbalist and creative inquirer. Connect with her at www.alifeofpractice.com

Sara Eisenberg grapples with honesty and kindness in daily life in Baltimore, where she practices as a healer, herbalist and creative inquirer. Connect with her at www.alifeofpractice.com

Do you have a story to share? Of course you do.

The Inconvenient Allure of Solitude by Guest Storyteller Maia Macek

I didn’t have my phone to take a picture as I sat by the river at dusk and watched the waves roil up against the rocks of the shore. A part of me felt like I was supposed to capture the moment and post to social media about it, in relentless entrepreneurial spirit, showing the world what I’m up to, a life coach publicizing her life in the modern currency of display.

I didn’t have my phone to take a picture as I sat by the river at dusk and watched the waves roil up against the rocks of the shore. A part of me felt like I was supposed to capture the moment and post to social media about it, in relentless entrepreneurial spirit, showing the world what I’m up to, a life coach publicizing her life in the modern currency of display.

As I looked out at the lighthouse, impossibly perched on an outcropping, with the Hudson River endlessly fleeing into the distance, my mind, ever that of the writer, ceaselessly cast out lines describing the view and my feelings about it.

I remembered childhood daydreams and long afternoons reading Victorian novels, ones filled with empty space and few characters. I could see myself installed in the lighthouse as its keeper, a dented tin teapot boiling water on the stove, me curled up in a window seat, holding a tattered book, feeling the solitude swirling all around me, a near-tangible companion.

I longed suddenly for the days before the internet, before this incessant drive to always be plugged in. I longed for the days before electricity, even.

Days and nights filled with inconvenience, maybe, but also full of the presence of something deeper.

Full of a presence that I sometimes worry I have lost, that the world has lost.

Until I sit, alone on a wind-blown day, the screeching of gulls swooping overhead, and I realize that true solitude is always here, waiting for me to visit.

Maia Macek is a Personal Liberation Coach who, after connecting with her own calling through a series of personally defining triumphs and mishaps, now guides her clients to unleash their true gifts, so they can live a life better than they even realize they deserve.

Maia Macek is a Personal Liberation Coach who, after connecting with her own calling through a series of personally defining triumphs and mishaps, now guides her clients to unleash their true gifts, so they can live a life better than they even realize they deserve.

Editor's note: I'm so pleased that #365StrongStories gave me a chance to meet Maia (I saw one of her thoughtful Facebook posts and knew I wanted to include her voice in the project). My community and I would love to hear your story too. Apply to become a #365StrongStories writer! Submit to #365StrongStories

As I Remember It by Guest Storyteller Ginny Taylor

As I remember it, three of us physician assistant students sat around a table, a group project before us, “What is Child Abuse?”

It was 1979. Child abuse was just emerging then - even though it has been in the world for thousands of years - as something criminal. Definitions appeared in texts with photos of cigarette burns on young arms, of babies’ bottoms blistered from hot water.

As I remember it, three of us physician assistant students sat around a table, a group project before us, “What is Child Abuse?”

It was 1979. Child abuse was just emerging then - even though it has been in the world for thousands of years - as something criminal. Definitions appeared in texts with photos of cigarette burns on young arms, of babies’ bottoms blistered from hot water.

As PA students, we needed to recognize these signs to treat them as burns and referrals to social workers. This was physical abuse.

But then there was also this other term, sexual abuse. Old men flashing children. Rape. Molestation.

And suddenly, for the first time in ten years, a memory resurfaced. A man old enough to be my grandfather. A trusted camp counselor, a man we called Uncle Jim. Positioning me, my back to him so I couldn’t see his face. His hand between my thighs. Groping the crotch of my bathing suit. Fondling.

Then, on the heels of this memory, a realization hits me.

I had been molested. In 1969 while at a summer church camp, I had been sexually abused.

And I say to my group, “This happened to me.”

At least, I think I say this aloud, for it’s always at this point my memory blurs. I know I say it to myself. And I know there is silence afterwards.

Perhaps it’s silence from the group. But even if they had spoken, what would they have said? We were only being trained on treating the physical signs. We were years away from inserting PTSD into our lexicon. We are still are years away from de-stigmatizing mental illness.

I don’t blame my group of peers for not speaking up in my watery memory, just as I now no longer blame myself for the decades of silence that followed. All of us were only coping the best we could with the tools we had.

Just like that molested girl… Just like that 10-year-old girl who, when Uncle Jim let her go, ran down the path to the swimming pool and dove deep… Just like that girl who resurfaced still holding her breath.

Women of Wonder founder Ginny Taylor teaches holistic practices like those in the WONDER COMPASS Story Art Pages, that can help women become the heroine of their own healing journey.

of Wonder founder Ginny Taylor teaches holistic practices like those in the WONDER COMPASS Story Art Pages, that can help women become the heroine of their own healing journey.

In recognition of National Sexual Assault Awareness month, special pricing on the WONDER COMPASS Story Art Pages is available.

Luis: A Study in Breath by Guest Storyteller Liz Hibala

It was a simple passing by most standards.

A friend’s cat, Luis, died. I knew him in a cursory way. He was an old fellow when I met him, an orange tabby with bowed front legs and a raspy smoker’s meow. He had a remarkable, intentional presence even when he clumsily circled my lap looking for the precise place to lower his ancient bones. As if to make full contact, he kneaded my legs along the way, claws extended, completely unaware or unconcerned the pain this ritual brought. He was himself.

It was a simple passing by most standards.

A friend’s cat, Luis, died. I knew him in a cursory way. He was an old fellow when I met him, an orange tabby with bowed front legs and a raspy smoker’s meow. He had a remarkable, intentional presence even when he clumsily circled my lap looking for the precise place to lower his ancient bones. As if to make full contact, he kneaded my legs along the way, claws extended, completely unaware or unconcerned the pain this ritual brought. He was himself.

Here, then not here, totally dependent upon the absence of an inhaled breath.

We move through time and space on ephemeral wings of breath. Experience and emotion, relationships and solitude - all dependent upon the repetitive motion of inhale and exhale. It is breath that maintains our presence here, it is breath that connects us to all life. At times intentional, mostly automatic, our breath is a constant companion. It moves with us through joy and struggle, triumph and heartbreak, with unwavering loyalty. With each breath, change. Each breath, a unique motion of its own. A microcosm of cosmic movement and eternal change.

I sit in the corner of my couch, writing. One of my cats lounges against my leg in a quiet, seemingly contented mood, drifting in and out of sleep. His long black fur gently rises and falls with each breath. I marvel at the simplicity of this scene and the simultaneous enormity that it holds. A quiet morning, a soft peacefulness, and the rhythmic movement of muscle directing air.

It’s all in the breath.

Liz Hibala is an emerging Crone, Reiki Master, and author living in the mountains of western Montana. Learn more about her book Óran Mór and her Reiki practice.

Liz Hibala is an emerging Crone, Reiki Master, and author living in the mountains of western Montana. Learn more about her book Óran Mór and her Reiki practice.

Traveling Distances by Guest Storyteller Peggy Acott

Why had she taken a train out of Minneapolis instead of making a direct flight to Seattle? It postponed the inevitable conversation with Bea, true, but made the anticipation of it a torment, stretching out like the endless lines of cattle fence rushing past her window; she had spent the last several hours (last several days, if she was to be truthful) running over various scripts and monologues in her head of how she was going to approach the topic with Bea. Hell, I can’t just walk into her house after all this time and say “Hi! Guess what? Daddy’s alive, but not for long, and he wants to see you.” She groaned audibly though no one heard, unless her moan got picked up by the wind and was now startling some poor prairie dog family minding their own business in their den.

But Alice couldn’t deny that she had been happy to see him, terrified by his cancer prognosis. She, who avoided all things having to do with sickness and mortality; she, who could not summon up the courage to visit her mother (for she still thought of Adriane as her mother) until the week before she died; couldn’t bear to see her sick and failing. She knew Bea was furious with her, maybe even hated her. She felt an ugly, malignant sort of cowardice that she wouldn’t admit to anyone. Well, now she was getting paid back in spades.

Why had she taken a train out of Minneapolis instead of making a direct flight to Seattle? It postponed the inevitable conversation with Bea, true, but made the anticipation of it a torment, stretching out like the endless lines of cattle fence rushing past her window; she had spent the last several hours (last several days, if she was to be truthful) running over various scripts and monologues in her head of how she was going to approach the topic with Bea. Hell, I can’t just walk into her house after all this time and say “Hi! Guess what? Daddy’s alive, but not for long, and he wants to see you.” She groaned audibly though no one heard, unless her moan got picked up by the wind and was now startling some poor prairie dog family minding their own business in their den.

But Alice couldn’t deny that she had been happy to see him, terrified by his cancer prognosis. She, who avoided all things having to do with sickness and mortality; she, who could not summon up the courage to visit her mother (for she still thought of Adriane as her mother) until the week before she died; couldn’t bear to see her sick and failing. She knew Bea was furious with her, maybe even hated her. She felt an ugly, malignant sort of cowardice that she wouldn’t admit to anyone. Well, now she was getting paid back in spades.

Alice gazed out into the distance. The parched, dry ochre hills and plains were so opposite to the life she made in the lush Hawaiian Islands; this landscape seemed like the no-man’s land threshold separating her past and her present. Unbidden, her memories started to bubble up: Daddy teaching her about fireflies; dinners around the wooden kitchen table in the dining room or the picnic table in the back yard in summer; her mother reading to her and Bea at bedtime in the room they shared, the warm pool of light from the bedside lamp illuminating the page of Wind in the Willows and their mother’s concentrated expression.

Peggy Acott is a writer in many forms, who shamelessly takes advantage of the rainy weather in western Oregon to help maintain her (mostly) regular writing practice.

Peggy Acott is a writer in many forms, who shamelessly takes advantage of the rainy weather in western Oregon to help maintain her (mostly) regular writing practice.